RESEARCH

OVERVIEW

This site highlights the connections between an eighteenth-century book and an intriguing example of twenty-first century conceptual art, through the creation of a browser-based web application that connects their central concern. The book is William Bartram’s Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida (1791), and the work of art is Mark Dion’s Travels of William Bartram’s Reconsidered (Seeds, Fungi, and Invertebrates) (2008), an art project inspired by Bartram’s journeys. Both works, although separated by over two centuries of time, are preoccupied with taking inventory of the natural world. This project takes the interest in cataloging one step further, by creating an inventory of the emotional, affective responses in Bartram’s writing that result from his engagement with the forces of nature.

We read Bartram’s Travels in the southern US as a crucial template for subsequent writing about natural landscapes. Although the Travels are focused on the southeast, it (and works like it) nevertheless help frame the entire North American continent as a dangerously exotic space in need of cultivating, civilizing, and taming. Such works suggest that the West as we have come to mythologize it, i.e., as a wild and lawless frontier, is a continuation of an already established aesthetic trope. While scholarship about travel writing in the context of the larger problem of colonialism is abundant, less has been said about the literary and aesthetic devices that drive such texts. A central textual technique in such works is that of taking a peculiar and selective form of inventory. That is, throughout his Travels Bartram is not merely documenting his exciting journeys across the American wilderness; he is also cataloguing—in an itemized and detailed fashion—all of the interesting and perhaps previously unknown flora and fauna that he encounters as he proceeds. And yet this inventory is presented as if it were entirely divorced from the material apparatuses that were required for its successful execution. There is rare mention of collection boxes, procedures of collection, or tools of documentation, nor is there very often any private reflection from the narrator. On the whole, Bartram’s description unfolds as if it were emerging from an impartial and objective vantage point. And yet Bartram's emotional equilibrium is far from constant. Throughout this text, the tone oscillates between that of a contemplative Romantic appreciation of nature on the one hand and sudden bursts of terror on the other. Such moments are incredibly important for the way they disrupt the smooth, confident tone of the observer and consequently call into question his impartiality and, hence, authority. Calling attention to the material realities that Bartram neglects is precisely the corrective reading that Mark Dion highlights in his “Travels…Reconsidered.” In this fascinating project, Dion provides a different type of inventory. Consisting of vials, tubes, and other vessels necessary for botanical collection, Dion’s work foregrounds the material artifacts that accompany all acts of inventory but are rarely acknowledged in the actual text.

Here, we take Dion’s impulse one step further, by creating a complementary inventory of Bartram’s Travels. Our inventory does not attempt to keep track of flora and fauna, nor does it hope to itemize the different types of material equipment necessary to capture them, which is Dion's focus. Our project uses digital tools and virtual environments in an attempt to realize a less tangible—though crucially immanent—part of Bartram's endeavor. In a nod to what Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth term an "inventory of shimmers" in their introduction to the Affect Theory Reader (Duke 2010), our script collects the emotional or affective responses that such objects, experiences, and encounters elicit—an inventory of affect. ▲ back to topRESEARCH QUESTIONS

Each of three researchers who worked on this project has distinct but complementary scholarly interests and backgrounds, and the project was stronger for it. Some of our specific research questions are articulated below.

YVETTE MYLETT

As a scholar who’s recently been exploring the way scientific knowledge is refracted in literature at the turn of the 20 th century, I enthusiastically welcomed the opportunity to read, research, and analyze a key naturalist text that became a rich source of inspiration for Romantic poets. Bartram’s Travels probes the boundary between neutral observation and aesthetic appreciation–a boundary which becomes immediately porous in Bartram’s introductory chapter–so that scientific and artistic modes of inquiry are brought into conversation. Just four pages in, Bartram writes,

Shall we analyze these beautiful plants, since they seem cheerfully to invite us? How greatly the flowers of the yellow Sarracenia represent a silken canopy? the yellow pendant petals are the curtains, and the hollow leaves are not unlike the cornucopia or Amalthea’s horn; what a quantity of water a leaf is capable of containing, about a pint!

Bartram moves seamlessly from imaginative musings that deploy the figurative language structures of metaphor and simile to a more data-driven empirical observation that captures an object’s size. Indeed, I was often tripped up when encountering the phrase “is like” in his Travels: in some moments, I expected a fantastical simile only to be met with a more restrained comparison to another plant species. Other times, the comparison was expressed in such a way that I couldn’t decide whether it was a recorded detail or a heightened appreciation of beauty. While Bartram seeks to faithfully record the detail of his surrounding environment, his descriptions frequently blend aesthetic appreciation with scientific language. These stunning lapses–of stricter visual transcription into more aesthetic frames for the environment he observes and vice versa–highlight the intimacy that exists between scientific cataloguing and the comparative gestures of figurative language. In taking our own inventory of these affective moments, we can understand that Bartram is not just the autonomous, neutral, or transparent observer he aspires to be; rather, we now see the extent to which Bartram is a figure who sways with his environment, and whose observational authority becomes fragile as the environment itself pushes, pulls, and paws at his seemingly detached stance.

The presence of aesthetic appreciation and impulses toward imaginative figuration can be read as something else besides a flaw in this scientific venture. These artistic moments might be understood to function productively by calling attention to the limitations of scientific observation and knowledge by finding the places where it fails to tell the full story. It can also highlight the constructed and embedded nature of any endeavor that espouses neutrality. Because the rhetoric of what’s “natural” or scientifically factual is often used to encode oppressive attitudes toward race, gender, and sexuality, it’s useful to see where the scientific reach has exceeded its grasp. The artistic presence may illuminate, then, the constructions and world-building projects that can lurk, entangled in ventures that work to objectify and domesticate–in this case, the wild spaces of America and its indigenous population, who are exoticized throughout the text. Hopefully, it can make space to re-imagine the procedures and theories of scientific inquiries that enforce such destructive encounters.

MAX SCHLEICHER

Inventory of Affect combines close and distant reading to explore how emotional tenor is tied to the naturalist William Bartram's classification of a landscape and engagement with native people. The project works to make visible the emotional component of a naturalist at work, while also drawing attention to the history of colonialism and resource exploitation inherent in such work. This project highlights the two-way street that makes digitally-infused literary analysis so intriguing. On the one hand, it uses digital tools to read at-scale and visualize the relationship of hundreds of emotional statements by John Bartram; on the other hand it uses humanistic inquiry to explore the way technology and discourse have historical hegemony baked into them in ways that define what Bartram thinks possible to know, classify, and even sympathize with.Inventory of Affect has resonated closely with my own creative and scholarly work. While reading Bartram’s Travels, I annotated 65 sentences where the author stands at an elevated point and waxes rhapsodic on the view extending before him. As a poet and scholar of poetry, this tendency of Bartram’s struck me as remarkably similar to the poetic tradition of so-called prospect poetry (or topographic poetry), typified by William Wordsworth’s Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey, where a poet stations themself on a high vantage and reflects on what they see in the countryside. This tradition was at its peak during the time of Bartram’s writing, and one can see how the poetic gaze in Bartram’s work is combined with a colonial one. Bartram often reflects on the availability of the resources he sees in the view just as he reflects on its natural beauty. This project has helped me to make a historical connection between prospect poetry and the explorer-naturalist’s gaze.

As my creative work is focused on the depleted landscapes of the Rust Belt, this project allowed me an opportunity to rewind the clock—so to speak—and immerse myself in landscape writing from an era when American landscape was written about as resource rather than depletion. I found myself contemplating the interesting double meaning in the word “prospect” as it applies to prospect poetry: the word’s meaning as both a vantage point and a sense of opportunity is present in the work of Bartram. Bartram looks from a prospect point and sees before him the prospect of a settled America, whose wildlife has been named and classified. As a poet who writes landscape poetry now, I have gained a deeper sense of the irony it takes to work in this tradition. Where Bartam’s gaze looks to the future, poets like myself see the prospect of cities that lost half their population and the bulk of their jobs since the 1970’s. For the landscape writer in the twenty-first century, one is living out the unimaginably depleted ending that Bartram could not have foreseen.

As a junior scholar, I found that Inventory of Affect and Travels of William Bartram Reconsidered provided me with compelling examples of how to engage with difficult work. These projects both take on some risk. They attempt to re-embody Bartram’s problematic process, but they do so in order to re-contexualize it for the audience’s benefit. Inventory of Affect does so at the sentence level, building a moment-by-moment index of Bartram’s emotional states and exploring the relationship between his affect and his settler-colonial ideology; Mark Dion’s work brings the menial physical labor of the naturalist to the forefront as an artistic project for museum-goers to see the kinds of specimens (e.g., plastic debris) Bartram might collect today. Both of these projects show how artists and scholars can recontextualize problematic work of the past in a careful, playful way that allows the audience to engage with its difficult history.

LISA SWANSTROM

In distinct but complementary ways, Bartram and Dion explore the beauty and construction of nature. Through their vivid descriptions of flora and fauna and their blunt depictions of raw emotional encounters, both texts raise uncomfortable questions about colonization, development, and the role of the human within creation. As high as the stakes of both texts are, however, the importance of wonder, curiosity, and playfulness is fundamental to their success. For example, Bartram's descriptions of the animals he encounters in Florida are often outrageously hyperbolized. He describes an alligator he espies as if it were a dragon: "Clouds of smoke issue from his dilated nostrils. The earth trembles with his thunder”—and proceeds to describe the terrifying sound the creatures make in chorus: “the Thunder of the Alegators, roaring all around us, & for many Miles."

In Travels...Reconsidered, Mark Dion revises such moments for our own time, hilariously juxtaposing the tone and tenor of Bartram’s voice with the environment of the contemporary south.

In one such moment, “Bartram Canoe Triangle, December 1-3" (2007), Dion describes becoming lost on the river in southern Alabama, finally aided by two fishermen. The artist notes:As their running light disappeared around the bend we discovered that I had mistakenly not packed the tent. Me, experienced expedition camper, had left the tent and the map. Perhaps, I should cut back on the booze…Throughout the night our sleep was interrupted by the most outrageous wild sound. The mad screams of the great blue heron, owl hoots, critters rambling in the dry leaves and alligator calls. (51)

Attentive to the humorous aspects of both works, our project tracks Bartram’s emotional dips and spikes in order to gain a better understanding of how our affective responses to natural spaces have been structured aesthetically over time.

▲ back to topPROCESS

The three of us read Bartram’s Travels sentence by sentence, noting any instances of emotional vocabulary, suggestive syntax, noteworthy sentence structure, cadence/meter, and/or content. We each kept track of our observations in our own virtual “cabinets” in the form of Excel spreadsheets. After we combined our overall observations we discussed the most intriguing patterns. Among many others, we noted Bartram’s tendency towards emotional bursts of intensity when measured against the more normalized observational mode. We noted his tendency to couple emotion with religious conviction in response to the natural world; his tendency toward adjectival “heaping” when describing a particularly striking natural phenomenon; his use of the imperative mode to both isolate—and share (after all, the imperative implies a second person)—a moment of emotional intensity; his overuse of the exclamation point (!) to whip up enthusiasm when particularly inspired; & etc. We created a “next steps” document to think through different ways to approach coding some of these patterns in Python.Through the use of regular expressions, the Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK), and the Spacy package, were able to achieve several of our objectives. In particular, in a script called religious_emotion.py , we isolated sentences conveying religious emotion through a targeted vocabulary (e.g., Creator, Divine); in imperatives.py we pulled out sentences that employ the imperative mode (Behold! Look!); in punctuation.py we—easy fishing!—scooped out sentences with multiple exclamation points. We were also interested to see in this script that when when we isolated punctuation marks (e.g.: "!", "?" and ".") in order of occurrence, it provided a simple but effective way to illustrate the distribution of the text’s spiking emotional energy.

▲ back to topCHALLENGES and LIMITATIONS

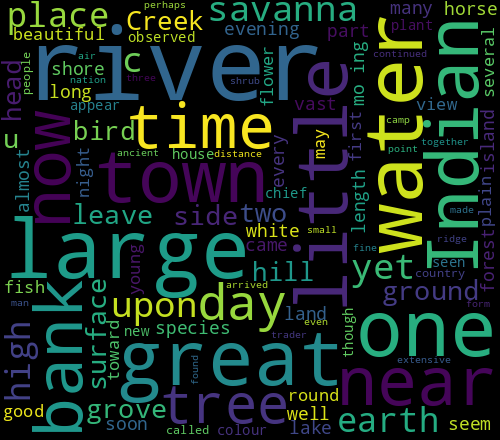

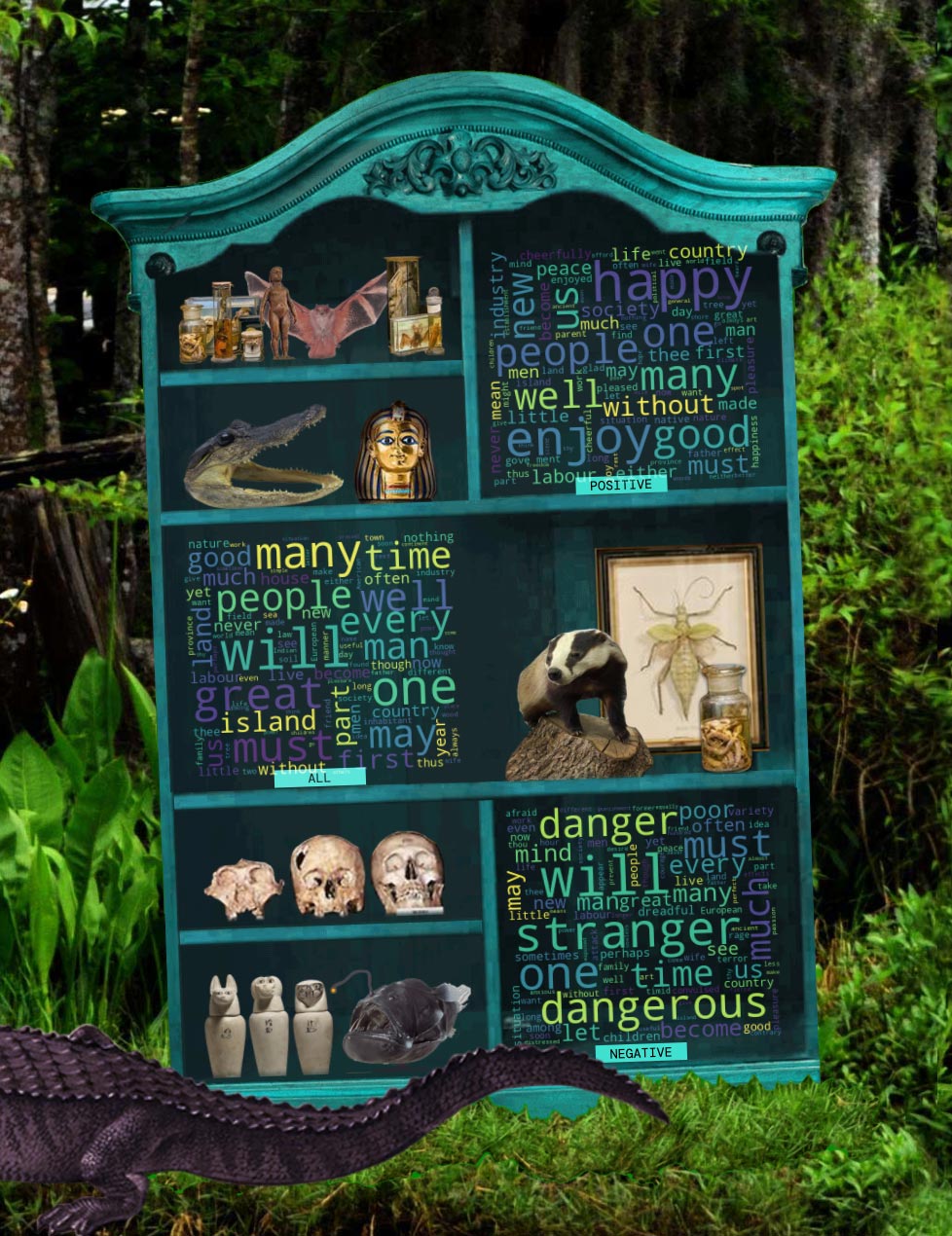

We were hopeful that the Spacy package would allow us to have greater control over the dependencies within sentences, but we were not entirely successful. For example, in natural_subjects.py we hoped to identify sentences in which an emotion occupies the subject position, but our code returned adjectives. Additionally, our imperative searches through Spacy were fruitless, and we ended up coding according to Bartram’s text specifically, even modifying the original to ignore false leads (such as the word “look” when it is used in the third person plural rather than as an imperative). These were most likely coding problems, so our next iteration will focus on debugging. Additionally, Spacy is time-intensive, especially online, through Flask. A search with Spacy takes nearly a full 60 seconds. When we removed its functionality we cut it down to under 10. For now, NLTK does our heavy lifting, even if it lacks Spacy's ability to identify dependencies. That is, the NLTK package is excellent at identifying parts of speech but not as limber when it comes to identifying whether a work occupies a nominative, dative, or accusative position. We intend to keep refining our approaches to the code. To keep the output streamlined in this first phase of the project, we have limited our results to include three word clouds: 1) sentences with positively charged emotional content; 2) all sentences in the text; 3) sentences with negatively valenced emotional content.

Each category is identified through sentence vocabulary. This is an easy route to take, but a more ambitious approach will be to identify patterns related to syntax, meter, and individual word choice. We have made some steps along these lines, and as NLTK allows for some level of metrical analysis, this is something we hope to pay more attention to as the project evolves.

▲ back to topRESULTS

Our results, then, for Bartram's Travels, are the following three word clouds. Word clouds, famously described in 2005 by Jeffrey Zeldman as the "new mullets" of the internet, have been fair targets of criticism since their popular debut in the early aughts. There are many good reasons for this, but their biggest drawback is a matter of presentation, in that they are often touted as self-evident demonstrations of content analysis. They are not. Word clouds mean nothing out of context; their utility depends upon a clear, honest breakdown of how they are generated, what they hope to measure (if anything), and their limitations. But the virtue of the word cloud stems from its ubiquity. They are familiar to us now—or have become so—and we know both how to read them and how to be suspicious of them. As long as these caveats are respected, the word cloud is an exceptionally efficient means of conveying information.

These imgages will likely be unsurprising for the reader who is familiar with Bartram's text. But for anyone who is new to the text, what might seem striking is that several words appear in both the positively and negatively focused clouds. Their frequency changes, to be sure, but the words that generate the most positively and negatively charged emotional intensity (according to our vocabulary) are the same. This provides a useful starting point for literary and historic analysis, for any reader.

▲ Figure 1: Positive, All, Negative wordclouds in Bartram's Travel's.

For example, Bartram is writing in the 18th century, and although the book is not published formally until 1791, the events it describes occur between 1773-1777, in the midst of the American Revolution. Bartram, a pacifict and Quaker, is largely silent about the larger political arena within which he operates, and his social commentary, when it occurs, emerges from his largely private and isolated immersion in natural spaces and is notable for its contradictions. All of it, however, conflicted as it is, deserves our attention: his admiration (and terror) of native peoples, his dismay (and resignation) regarding broken treaties, his frustration with (and dependence upon) the labor of enslaved people, his admiration of (and prudishness towards) women, his approbation (or disapproval—this depends not upon their political leanings but whether they have acted as good custodians to the plants on their property) of landholders and the estates they manage. And while the words "Indian" and "cheerful," for example, appear frequently in the positive image, the word "Indian" occurs even more frequently in the negative. (Note that these two words do not co-locate; that is, while Bartram writes of a "hostile" Indian and a "magnificent" Indian, he does not make mention of a "cheerful Indian." I've selected these two words here because of their similar frequency, and to point out that the words in a cloud are not syntactically joined, unless by accident.) This is not to say there is a simple mathematical correspendence to this emotional shift. Just as the word "clouds" is fairly meaningless without context, frequency in itself means very little. That said, the fact that the same words inspire both joy and terror for Bartram provides some evidence of a man of a mind divided, one who suffers painful fluxes as he recounts—but never resolves—conflicting emotional experience.

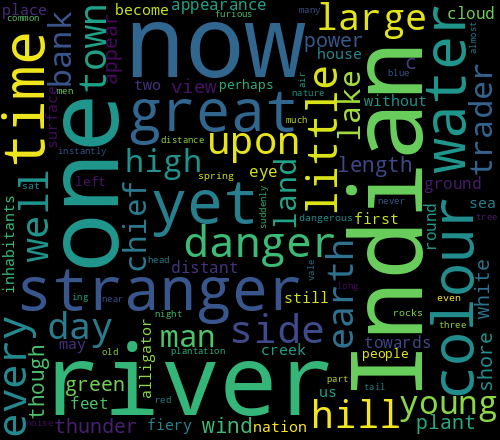

If we were to contrast this text to one more evenly apportioned in terms of affect—a work in which good is good and bad is bad and the area between them brooks no ambiguity—we would get quite different results. Even more interesting, perhaps, would be to compare these results to one of Bartram's contemporaries. When we load Hector St. John Crevecoeur's Letters from an American Farmer (1782), for example, we get an instructive distribution, as we can see in the following output:

Here two words leap out: "happy" and "people" in the positive and "stranger" and "danger" in the negative. Again, these words do not co-locate, but they provide fascinating points of contrast to Bartram's words. In Bartram's negative cloud, the word "stranger" is also prominent, and comparing the two notions of what counts as a "stranger" in the context of colonial settlement, both on a land holding and in the wilderness, would be a fruitful point of departure.

We offer this project in the spirit of helping a reader take first steps into an analysis rather than claiming it provides conclusive information. We believe it does the former. We firmly deny it does the latter. Indeed, we have our doubts about any such claims, especially when it comes to qualitative linguistic analysis. Big data does not always yield big results. And when it does, it necessarily occludes the subtle, nuanced approach that is required of close, careful reading. Digital Humanities projects are much more sensitive to this problem than are the large-scale machine learning projects undertaken by large technology companys. Even so, many DH projects that focus on literary analysis that provide superb metrics and brilliant conclusions often fail to connect to the very audience who would find their research most interesting: lovers of reading and students of literature. It is our sincere hope that our small-scale approach to distant reading, coupled with the playful interface, will help to allay this disconnect. It invites any reader—from the novice high school student to the established scholar—to consider the usefulness (and limitations) of digital tools, as well as the importance of emotional patterns in any literary text.

▲ back to topTECH SPECS

INVENTORIES OF AFFECT was created with the following tools:

Coding: Python 3.6

Flask

Pythonanywhere

NLTK, Spacy

Design: HMTL, CSS, Javascript/jQuery

CODE

The code used to make this project is all available in this dropbox folder. We've also included a few .txt files to try out. ▲ back to top

DESIGN

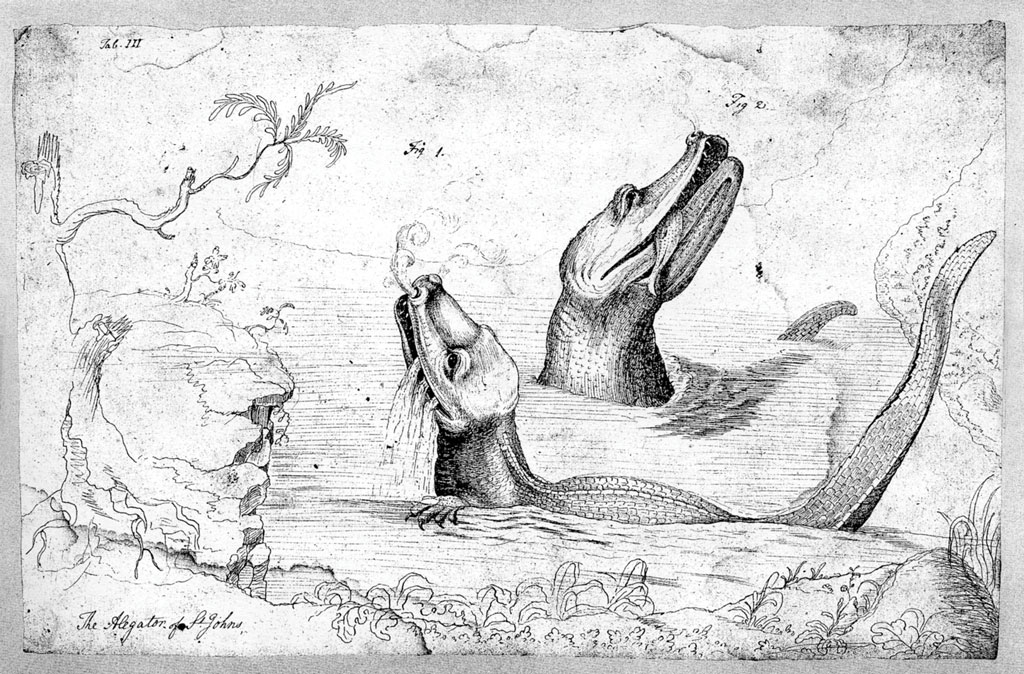

The central organizing motif is a distressed turquoise cabinet of wonders (Wunderkammer) stuck in a swamp. Each time a user loads a new text, three word clouds related to emotion emerge, embedded in the cabinet. To the left of the Wunderkammer an alligator, drawn by Bartram himself, emits "a cloud of smoke" from its nostrils (in keeping with Bartram’s descriptions of the beast). The cabinet's curiosities change slightly with each re-load.

If the word cloud is, indeed, the mullet of data visualization, we can think of no other intersection (Bartram-Florida-Dion) more appropriate to allow its fullest expression. Bartram’s prose is excessive—effuse, often stilted, and occasionally (if unintentionally) hilarious. Dion’s project on the other hand, which takes the form of a contemporary foray into the Floridian landscape using Bartram’s original text as a stylistic and thematic template, is overtly playful, juxtaposing as it does the artifacts of the 21st century American south with the language of the 18th century naturalist. To keep faithful to both Bartram’s excitement about the natural world and Dion’s more sly anthropological performance, we have chosen a playful mash-up of images for the project interface.

Our designer, Scott Svatos, did a fantastic job in creating a design that is, we hope, instantly recognizably as irreverent and absurd, yet inviting. Although Bartram’s work inspires this project, we have used the domain name “Inventories” of Affect, plural, in the hope of inviting users to upload any literary text in which the emotional content—baggage, even—has yet to be unpacked.

▲ back to topRESOURCES

Primary works

Marriott Library

Book. William Bartram’s Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida (Special Collections: Z232.5 .P4 B37).

UMFA

Sculpture. Mark Dion’s “Travels of William Bartram’s Reconsidered: Seeds, Fungi, and Invertebrates” (Non-circulating collection: UMFA 2011. 8.1A).

Additional resources

Marriott Library

Book. Charles Darwin’s The Expressions of the Emotions in Man and Animals (Rare Books: QP401.D3).

Book. Melissa Gregg and Gregory Seigworth's Affect Theory Reader. (General Collections: BF175.5.A35 A344 2010).

Book. John Wesley Powell’s The Exploration of the Colorado River and Its Canyons (Special Collections: Z232.5.P4 P6859).

Book. Colon South’s Out West, or, from London to Salt Lake City and Back (Special Collections: F595.S635 1884).

Book. Albert Tissandier’s Six mois aux Etat-Unis: the Drawings of Albert Tissandeier (Special Collections: NC139.T57 A4 1986).

Exhibit. “Are We There Yet? Westward Exploration and Travel in North America (Special Collections: Virtual Exhibit).

UMFA

UMFA1987.037.004 - .005 Eadweard Muybridge, Animal locomotion (plates 626 and 272), 1887, collotypes; UMFA1995.022.003, Muybridge, El Capitan, 3300 feet high, 1872, albumen print; UMFA19950022.004 Muybridge, Half Dome, 4750 feet high, 1872, albumen print. UMFA1977.090 U.S. Federal Forces Crossing the South Fork of the Platte River in Route to Utah Territory, 1858, ink on tracing cloth.

UMFA1999.17.1 - .25; UMFA2000.20.10; UMFA2002.39.6 - .15; UMFA2003.25.1 -.14; UMFA2003.26.1 - .16; UMFA2003.27.1 - .3; UMFA2003.30.1 - .12; UMFA2003.31.1 - .3; UMFA2004.25.1 - .5; UMFA2005.32.1 - .7; UMFA2005.34.1 - .13. Jeanette Klute, various titles, dates. Nature Studies (various).